Few days ago I've bought a USB keylogger to use on my own computers (explanation in french here). Since then, and as I'm sitting in front of a computer more than 12 hours a day, I've got plenty of time to test it.

Few days ago I've bought a USB keylogger to use on my own computers (explanation in french here). Since then, and as I'm sitting in front of a computer more than 12 hours a day, I've got plenty of time to test it.

The exact model I've tested is the KeyGrabber USB MPC 8GB. I've had to choose the MPC model because both my current keyboards are Apple's Aluminum keyboards. They act as USB hubs, hence requiring some sort of filtering so that the keylogger won't try and log everything passing through the hub (mouse, usb headset, whatever…) and will get only what you type.

My setup is close to factory settings: I've just set LogSpecialKeys to "full" instead of "medium" and added a French layout to the keylogger, so that typing "a" will record "a", and not "q".

First of all, using the device on a Mac with a French Apple keyboard is a little bit frustrating: the French layout is for a PC keyboard, so typing alt-shift-( to get a [ will log [Alt][Sh][Up]. "[Up]"? Seriously? The only Macintosh layout available is for a US keyboard, so it's unusable here.

The KeyGrabber has a nice feature, especially on it's MPC version, that allows the user to transform the device into a USB thumbdrive with a key combination. By default if you press k-b-s the USB key is activated and mounts on your system desktop. The MPC version allows you to continue using your keyboard without having to plug it on another USB port after activation of the thumbdrive mode, which is great. You can then retrieve the log file, edit the config file, etc.

Going back to regular mode requires that you unplug and plug back the KeyGrabber.

Applying the "kbs" key combo needs some patience: press all three keys for about 5 seconds, wait about 15-20 seconds more, and the thumbdrive could show up. If it does not, try again. I've not tested it on Windows, but I'm not very optimistic, see below.

I'm using a quite special physical and logical setup on my home workstation. Basically, it's an ESXi hypervisor hosting a bunch of virtual machines. Two of these VM are extensively using PCI passthrough: dedicated GPU, audio controller, USB host controller. Different USB controllers are plugged to a USB switch, so I can share my mouse, keyboard, yubikey, USB headset, etc. between different VMs. Then, the KeyGrabber being plugged between the keyboard and the USB switch, it's shared between VMs too.

Unfortunately, for an unidentified reason, the Windows 10 VM will completely loose it's USB controller few seconds after I've switched USB devices from OSX to Windows. So for now on, I have to unplug the keylogger when I want to use the Windows VM, and that's a bummer. Being able to use a single device on my many systems was one of the reasons I've opted for a physical keylogger, instead of a piece of software.

Worse: rebooting the VM will not restore access to the USB controller, I have to reboot the ESXi. A real pain.

But in the end, it's the log file that matters, right? Well, it's a bit difficult here too, I'm afraid. I've contacted the support at Keelog, because way too often what I see in the log file does not match what I type. I'm not a fast typist, say about 50 to 55 words per minute. But it looks like it's too fast for the KeyGrabber which will happily drop letters, up to 4 letters in a 6 letters word (typed "jambon", logged "jb").

Here is a made-up phrase I've typed as a test:

c'est assez marrant parce qu'il ne me faut pas de modèle pour taper

And here is the result as logged by the device:

cesae assez ma[Alt][Ent][Alt]

rrant parc qu'l ne e faut pa de modèl pour taper

This can't be good. May be it's a matter of settings, some are not clearly described in the documentation, so I'm waiting for the vendor support to reply.

Overall, I'm not thrilled by this device. It's a 75€ gadget that won't work properly out of the box, and will crash my Win 10 system (and probably a part of the underlying ESXi). I'll update this post if the support helps me to achieve proper key logging.

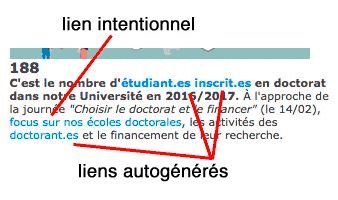

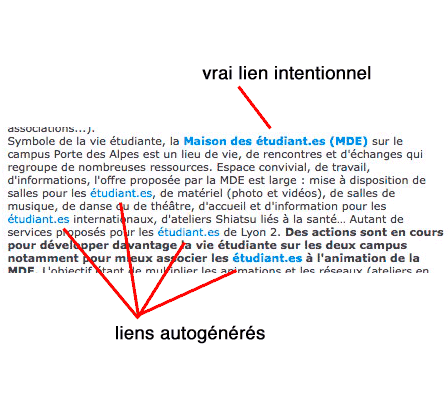

Malheureusement pour cette forme d’écriture, les supports numériques prévalent de plus en plus, et la maîtrise du support disparaît presque totalement au profit d’intermédiaires, de médias, qui peuvent décider d’améliorer l’expérience utilisateur sans demander son avis à l’auteur initial. Que cet intermédiaire soit un logiciel bureautique, un CMS, une plateforme de réseau social, une application de SMS, une messagerie instantanée, etc. nombreux sont ceux qui vont s’arroger le droit d’activer les URL qu’ils détectent dans les contenus soumis. Ainsi, quand un auteur écrit que « les étudiant.es peuvent se porter candidat.es au concours d’infirmier.es », il est bien possible que le média de publication informe les lecteurs que « les

Malheureusement pour cette forme d’écriture, les supports numériques prévalent de plus en plus, et la maîtrise du support disparaît presque totalement au profit d’intermédiaires, de médias, qui peuvent décider d’améliorer l’expérience utilisateur sans demander son avis à l’auteur initial. Que cet intermédiaire soit un logiciel bureautique, un CMS, une plateforme de réseau social, une application de SMS, une messagerie instantanée, etc. nombreux sont ceux qui vont s’arroger le droit d’activer les URL qu’ils détectent dans les contenus soumis. Ainsi, quand un auteur écrit que « les étudiant.es peuvent se porter candidat.es au concours d’infirmier.es », il est bien possible que le média de publication informe les lecteurs que « les

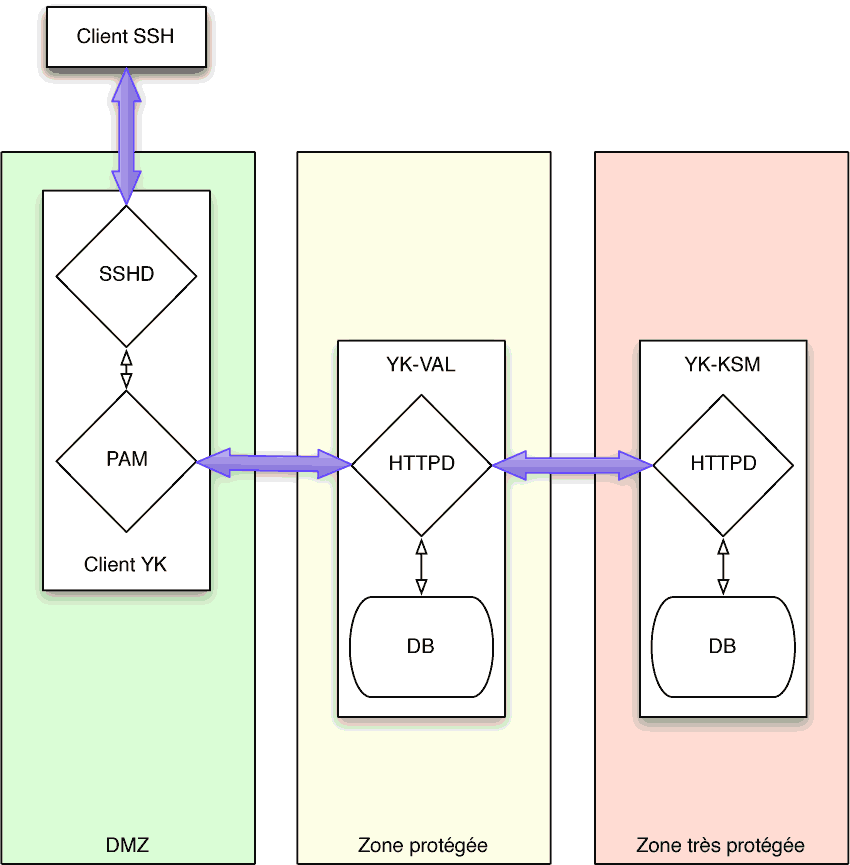

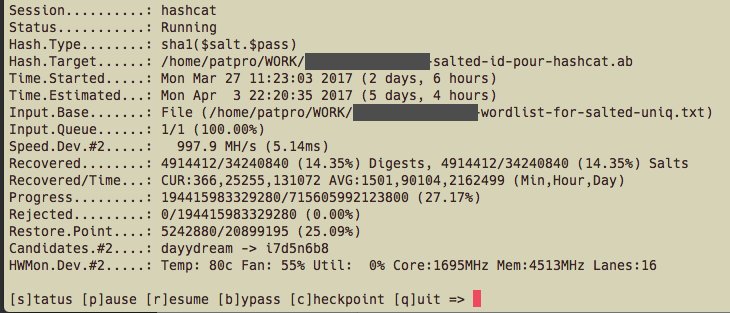

Dans deux articles précédents j'ai présenté la création d'un

Dans deux articles précédents j'ai présenté la création d'un